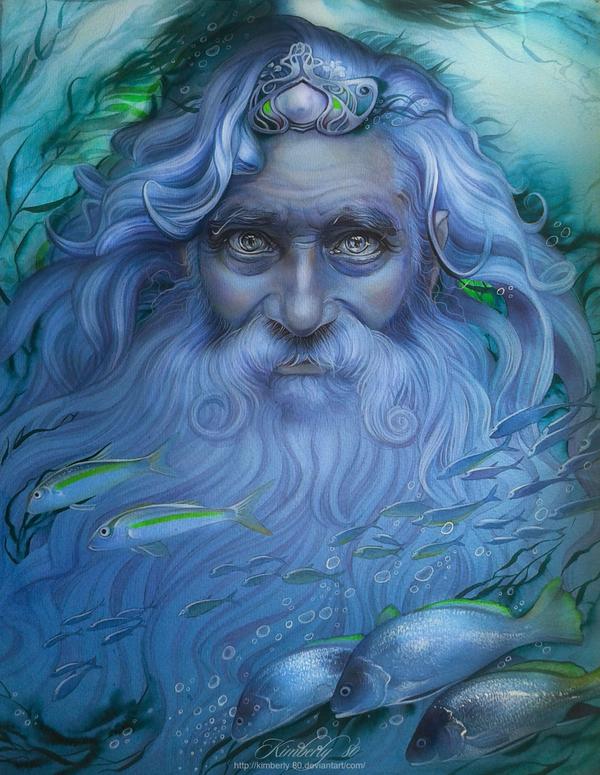

In this biweekly series, we’re exploring the evolution of both major and minor figures in Tolkien’s legendarium, tracing the transformations of these characters through drafts and early manuscripts through to the finished work. This week’s installment is the second in a mini-series exploring the Vala Ulmo, Lord and Wielder of Waters, Dweller of the Deep, the Pourer: the god at whose prompting Gondolin was founded and through whose protection Eärendil made his renowned journey to the Undying Lands.

In our last installment, we explored Ulmo’s character and personality, specifically looking at his close connection with Ilúvatar’s music and with water. In that article, I wanted to make especially clear that fact that Ulmo is unique among the Valar. He sees further, for one thing, and this allows him to approach difficult situations with a sense of grace, justice, and good that are on a cosmic scale. His judgments are therefore often wiser than those of his fellow Powers of Arda; Ulmo plays the long game. I think this also means that Ulmo, more than any other Valar, knows precisely what is at stake in the war against Morgoth. He isn’t deceived: he knows the threat Morgoth poses, as well as the fact that Ilúvatar is more than capable of handling any weapon or machination the Enemy has in his wheelhouse.

Today, we’re going to continue our examination of Ulmo by taking a look at the role he plays in the historical narrative of Arda.

Ulmo first begins to stand out amongst the Valar because of his desire for solitude. He is one of the few Valar who remains romantically unattached, but he also chooses to live in “the Outermost Seas that were beyond the Outer Lands” (The Book of Lost Tales 1, hereafter BLT1, 67). Those Seas “have no tides, and they are very cool and thin, that no boat can sail upon their bosom or fish swim within their depths” (BLT1 68). There Ulmo lives alone, brooding and orchestrating from a distance, unobtrusively moving pieces on the vast gameboard of history. While the other Valar dwell together in the light and peace of Valinor, Ulmo begrudges any time he has to spend at their high feasts and councils, and often slips away from these gatherings in annoyance (BLT1 67).

He also specifically chooses to leave the governing of the seas to his vassal Ossë. This in particular is a choice and circumstance that Tolkien found perplexing—he was never completely sure whether Ossë was a bitter servant who fretted at his boundaries or simply a high-spirited entity whose charisma couldn’t always be contained by bonds of duty and loyalty.

The tension between these two powers—and the tension in Tolkien’s treatment of it—first appears upon the awakening of the Eldar in Middle-earth. Almost at once, the problem emerges. All of the Valar are thrilled, of course. Upon hearing the news, even Ulmo rushes to Valinor from his hidden depths, his face revealing his overwhelming joy (BLT1 123). But here, Tolkien is faced with a question. Some of the Valar want the Eldar to be brought over to join them in the Undying Lands. What about Ulmo?

At first, Tolkien writes that Ulmo is thrilled with the idea—and indeed, it is largely through Ulmo’s ingenuity that the Elves eventually make it to Valinor. In this early tale, the Eldar are transported to a secret, magical island, where a pod of whales (or, in one draft, a single whale by the name of Uin) is directed by the Lord of Waters to carry the island across the Sea. Ossë, driven by jealousy, stops the island and because no one, even Ulmo, is his match in “swimming and in deeds of bodily strength in the water,” he is able to chain the island to the sea floor within sight of Valinor (BLT1 129). Conflict ensues, but Ossë is pressed into teaching the Eldar the craft of shipbuilding, and they are thus able to reach their final destination. Once there, the Elves are joined on the shores by Ulmo: he “came and sat among them as aforetime in Tol Eressëa, and that was his time of greatest mirth and gentleness, and all his lore and love of music he poured out to them, and they drank it eagerly” (BLT1 136). Here we see the first seeds of Ulmo’s relationship with the Eldar, which will later sprout and blossom in unexpected ways.

Buy the Book

Drowned Country

Of course, Tolkien didn’t let his first idea rest. He took many years to decide exactly what action would best suit Ulmo’s character and motivations. In the published Silmarillion, for example, Ulmo actually tells Ossë to chain the island to the sea floor. His foresight warns him that there is great danger in bringing the Elves to the Undying Lands before they have had a chance to fully live on their own, and so he works to thwart what he sees as the foolish, eager haste of the other Valar. He only grudgingly allows his kin to have their own way, realizing that he can’t oppose them alone.

We can take this as a sort of starting point from which to look at Ulmo’s attitude towards the Elves. When the Noldor rebel under Fëanor and leave Valinor with the curse of the Valar at their backs, it is Ulmo who, according to “The Tale of the Sun and Moon,” is the most saddened by the departure of the Eldar, and by the seashore he calls to them and makes sorrowful music; he doesn’t become angry, though, because he “was foreknowing more than all the Gods, even than great Manwë” (BLT1 198). This narrative crafts an Ulmo whose knowledge of the future and Ilúvatar’s plan warns him of a great sorrow to come if the Elves dwell among the gods—an Ulmo who mourns and weeps over broken ties and angry words even as he is able to accept that the will of Ilúvatar will ultimately guide all paths to their rightful destination.

Interestingly, it is also Ulmo who, especially in the early drafts, condemns the Valar for choosing to hide the Undying Lands and withdraw from Middle-earth. Tolkien softens Ulmo’s criticism later. As I’ve said in other columns, the Valar of Tolkien’s first stories were more fallible and “human” in their attitudes and actions—more like the gods of Greece and Rome than the angelic, high beings they later become. With that change, Ulmo’s criticism is lessened because the Hiding of Valinor is now simply another important step in Ilúvatar’s plan, and not a selfish mistake made by angry, short-sighted rulers.

All the same, Ulmo more than any other preserves his original love for the Eldar after their rebellion. According to The Book of Lost Tales 2, Ulmo let his music run through all the waters of Middle-earth because he “of all the Valar, still thought of [the Eldar] most tenderly” (78). One text even remarks that Ulmo loved the Elves more “coolly” than Aulë, but “had more mercy for their errors and misdeeds” (Morgoth’s Ring, hereafter MR, 241). That tenderness and mercy guides Ulmo’s actions from this point forward. He begins to withdraw from the other Valar to an even greater extent, including from Manwë, with whom he had been particularly close (MR 202).

Time passes. Ulmo continues to divinely intervene in history—mostly through small touches that by themselves wouldn’t mean much, but that together represent a powerful movement towards the fulfillment of Ilúvatar’s Music. He inspires Turgon to build Gondolin, and by his guidance assures that the Elf is able to find his way back to the secret pass in the mountains (The War of the Jewels, hereafter WJ, 44-45; The Lost Road, hereafter LR, 278). Later, he ensures that Huor and Húrin stumble onto the path to the Hidden City (WJ 53). He prompts mariners to regularly attempt to find the Hidden Lands, and so orchestrates the journey of Voronwë, whom he later saves from the wrath of Ossë and guides to met Tuor in time to providentially lead him to Gondolin (WJ 80).

Ah, Tuor. It is, I think, in the story of Tuor and his son Eärendil that Ulmo’s influence is clearest. The Lord of Waters had much in store for the young man; he sets it all in motion on that fateful day when he rises out of the deep on the shore of the Land of Willows. But his plan was long in motion. We’ve already mentioned the preparation of Turgon, Gondolin, and Voronwë for Tuor’s destiny: until this powerful meeting in the Land of Willows, however, Ulmo has simply been prodding Tuor along the path with vague desires, faint longings and spurrings that the Man himself does not quite comprehend. Now, afraid that Tuor will become apathetic and settle down to a hermetic life in a beautiful and peaceful land, Ulmo comes to a decision. He will speak to Tuor in person.

Tuor is, naturally, petrified. In Tolkien’s various descriptions of the moment, the reader can almost hear the running of the current broken by sudden upheaval as the Dweller in the Deep breaks the steady rhythm, the rush of waters pouring from him as he steps onto the shore, towering, formidable, glorious. The Wielder of Waters sounds his horn, and:

Tuor hearkened and was stricken dumb. There he stood knee-deep in the grass and heard no more the hum of insects, nor the murmur of the river borders, and the odour of flowers entered not into his nostrils; but he heard the sound of waves and the wail of sea-birds, and his soul leapt for rocky places… (The Fall of Gondolin, hereafter FoG, 46)

Then Ulmo speaks. Tuor “for dread […] came near to death, for the depth of the voice of Ulmo is of the uttermost depth: even as deep as his eyes which are the deepest of all things” (FoG 46). The god commands Tuor to journey to Gondolin and bring a message to Turgon there. And then he prophesies, revealing the end goal of all his workings. “Yet maybe thy life shall turn again to the might waters,” he says; “and of a surety a child shall come of thee than whom no man shall know more of the uttermost deeps, be it of the sea or of the firmament of heaven” (FoG 46-47). So the birth of Eärendil and his great Journey is foretold in a moment of crisis.

Tuor obeys all that Ulmo asks of him, though his heart longs to return to the sea. All through the course of his life the hand of Ulmo rests on him, giving him presence and power, turning the hearts of people towards him, and protecting him so that in time, Tuor at last takes a ship and sets sail on the high waters, never to be heard from again.

Even now Ulmo does not rest. Eärendil, the son of Tuor and Idril, is the crowning point of this long game. His love for the Eldar has never yet flagged or grown faint, though he recognizes their wrongs. He has been patient over the long, long years. He has watched Morgoth rise, spurred by his vengeful vendetta, to crush the Noldor under his heel. He has seen the Elves war amongst themselves, slaughtering each other in greed. He has witnessed the desperate attempts of a brave few to seek out the aid of the Valar. Never once has he moved too soon, or acted overeagerly.

Now Eärendil prepares to set sail for the Undying Lands, and Ulmo, Lord of Waters, is with him. The god protects the renowned mariner from the roiling waters and the reckless energy of Ossë. When valiant Elwing throws herself into the sea with a Silmaril to bring aid to her husband, Ulmo bears her up and transforms her into a sea-bird so that she comes safely through the storms to the arms of Eärendil.

Then, as Eärendil wanders towards Taniquetil, his way-worn shoes shining with the dust of diamonds, Ulmo strides into the council of the Valar, and in stirring words he speaks for Eärendil, begs that the Valar pay heed to his errand (LR 360). And they do. Because of the prayers of Ulmo they listen to the message of the herald, the great arbiter, Eärendil, and after many hundreds, even thousands, of years of silence and inaction, they move against Morgoth and prove that Ilúvatar has not forgotten his children. So Ulmo’s great mission is completed. Through patience and wisdom he has succeeding in moving the Valar to pity and mercy for the ones he loves, and in so doing he has also accomplished the will of Ilúvatar, bringing the world just a bit closer to the harmonious music for which it is destined.

***

When I look over the entirety of Ulmo’s story, I am struck by the way in which his ability to keep the big picture in mind allows him to react to situations with wisdom, justice, and mercy. Ulmo is, in all sincerity, a deep character. He is slow to anger and slow to react rashly because he knows that the story being told is larger than a single moment. He’s willing to forego petty quibbles because in the long run, a person is more than a single action, a group of people more than a single mistake. These things are, ultimately, very small when compared with the entire course of history.

However, this doesn’t cause him to lose sight of the individual; Ulmo understands the power of a single person to change the course of history and he is more than willing to work through them to achieve Ilúvatar’s will. Turgon, Voronwë, Tuor, Eärendil, Elwing…Ulmo’s wisdom plants desires in their hearts, supporting and upholding them in many trials. Through his support they are able to achieve greatness, becoming some of the most iconic players in the great tale whose many threads run through the history of Middle-earth, and beyond.

But Ulmo’s grace and love isn’t only extended to those for whom he has great plans. Tales say that he often appears to seafarers, and takes those who are lost at sea to himself, where they are forever remembered even after the world has long forgotten them.

Megan N. Fontenot is a Tolkien scholar and fan who is thankful for the light and hope that can be found in Middle-earth, as well as the encouragement of the lessons the characters embody. Catch her on Twitter @MeganNFontenot1 and feel free to request a favorite character while you’re there!